Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II

| F-35 Lightning II | |

|---|---|

|

|

| An F-35A Lightning II, marked AA-1, lands at Edwards Air Force Base, California | |

| Role | Stealth multirole fighter |

| First flight | 15 December 2006[1] |

| Introduction | 2014 (USMC)[2][3] 2014 (USAF) 2016 (USN)[4][5][6] |

| Status | Under development, in flight testing |

| Produced | 2003–present |

| Number built | 13 flight-test aircraft;[7][8] 15 LRIP aircraft on order. |

| Unit cost | US$191.9 million (flyaway cost for FY 2010)[9] |

| Developed from | Lockheed Martin X-35 |

The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II is a fifth-generation, single-seat, single-engine stealth multirole fighter that can perform close air support, tactical bombing, and air defense missions.[10] The F-35 has three different models; one is a conventional takeoff and landing variant, the second is a short take off and vertical-landing variant, and the third is a carrier-based variant.

The F-35 is descended from the X-35, the product of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. Its development is being principally funded by the United States, with the United Kingdom and other partner governments providing additional funding.[11] It is being designed and built by an aerospace industry team led by Lockheed Martin with Northrop Grumman and BAE Systems as major partners.[11] The X-35 demonstrator first flew in 2000,[12] and the F-35's first flight took place on 15 December 2006.[13]

The United States intends to buy a total of 2,443 aircraft for an estimated US$323 billion, making it the most expensive defense program ever.[14] The USAF's budget data in 2010 projects the F-35 to have a US$89 million flyaway cost over its planned production of 1,753 F-35As.[9] Lockheed Martin expects to reduce government cost estimates by 20%.[15]

Contents |

Development

JSF Program history

Requirement

The JSF program was designed to replace the U.S. military's F-16, A-10, F/A-18 (excluding newer E/F "Super Hornet" variants) and AV-8B tactical fighter aircraft. To keep development, production, and operating costs down, a common design was planned in three variants that share 80% of their parts:

- F-35A, conventional take off and landing (CTOL) variant.

- F-35B, short-take off and vertical-landing (STOVL) variant.

- F-35C, carrier-based CATOBAR (CV) variant.

The F-35 is intended to be the world's premier strike aircraft through 2040, with close- and long-range air-to-air capability second only to that of the F-22 Raptor.[10] The F-35 is required to be four times more effective than existing fighters in air-to-air combat, eight times more effective in air-to-ground combat, and three times more effective in reconnaissance and suppression of air defenses – while having better range and requiring less logistics support.[16]

Lockheed Martin has suggested that the F-35 could also replace the USAF's F-15C/D air superiority fighter and F-15E Strike Eagles in the air superiority role.[17]

With takeoff weights up to 60,000 lb (27,000 kg), the F-35 is considerably heavier than the lightweight fighters it replaces. In empty and maximum gross weights, it more closely resembles the single-seat, single-engine Republic F-105 Thunderchief, which was the largest single-engine fighter of the Vietnam era.

Origins and selection

The Joint Strike Fighter evolved out of several requirements for a common fighter to replace existing types. The actual JSF development contract was signed on 16 November 1996.

The contract for System Development and Demonstration (SDD) was awarded on 26 October 2001 to Lockheed Martin, whose X-35 beat the Boeing X-32. Although both met or exceeded requirements, the X-35 exceeded each requirement. The design was considered to have less risk and more growth potential.[18] The designation of the fighter as "F-35" came as a surprise to Lockheed, which had been referring to the aircraft in-house by the designation "F-24".[19]

Design phase

Based on wind tunnel testing, Lockheed Martin slightly enlarged its X-35 design into the F-35. The forward fuselage is 5 inches (130 mm) longer to make room for avionics. Correspondingly, the horizontal stabilators were moved 2 inches (51 mm) rearward to retain balance and control. The top surface of the fuselage was raised by 1 inch (25 mm) along the centerline. Also, it was decided to increase the size of the F-35B STOVL variant's weapons bay to be common with the other two variants.[18]

The F-35B STOVL variant was in danger of missing performance requirements in 2004 because it weighed too much – reportedly, by 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg) or 8 percent. In response, Lockheed Martin added engine thrust and shed more than a ton by thinning the aircraft's skin; reducing the size of the common weapons bay and vertical stabilizers; re-routing some thrust from the roll-post outlets to the main nozzle; and redesigning the wing-mate joint, portions of the electrical system, and the portion of the aircraft immediately behind the cockpit.[20] Many of the changes were applied to all three variants to maintain high levels of commonality. By September 2004, the weight reduction effort had reduced the aircraft's design weight by 2,700 pounds (1,200 kg).[21]

On 7 July 2006, the US Air Force officially announced the name of the F-35: Lightning II, in honor of Lockheed's World War II-era twin-prop P-38 Lightning[22] and the Cold War-era jet, the English Electric Lightning.[23][N 1] English Electric Company's aircraft division was a predecessor of F-35 partner BAE Systems. Lightning II was also an early company name for the aircraft that became the F-22 Raptor.

On 19 December 2008, Lockheed Martin rolled out the first weight-optimized F-35A (designated AF-1). It is the first F-35 to be produced at a full-rate production speed and is structurally identical to the production F-35As that will be delivered starting in 2010.[24]

As of 5 January 2009, six F-35s are complete, including AF-1 and AG-1, and 17 are in production. "Thirteen of the 17 in production are pre-production test aircraft, and all of those will be finished in 2009," said John R. Kent, acting manager of F-35 Lightning II Communications at Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company. "The other four are the first production-model planes, and the first of those will be delivered in 2010 to the U.S. Air Force, and will go to Eglin."[25] On 6 April 2009, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates proposed speeding up production for the US to buy 2,443 F-35s.[26][27]

On 21 April 2009 media reports, citing Pentagon sources, said that during 2007 and 2008, computer spies managed to copy and siphon off several terabytes of data related to F-35's design and the electronics systems, potentially enabling the development of defense systems against the aircraft.[28] However, Lockheed Martin has rejected suggestions that the project has been compromised, saying that it "does not believe any classified information had been stolen".[29]

On 9 November 2009, Ashton Carter, under-secretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics, acknowledged that the Pentagon "joint estimate team" (JET) had found possible future cost and schedule overruns in the project and that he would be holding meetings to attempt to avoid these.[30] On 1 February 2010, Gates removed JSF Program Manager Marine Maj. Gen. David Heinz and withheld $614 million in payments to Lockheed Martin because of program costs and delays.[31][32]

On 11 March 2010, a report from the Government Accountability Office to United States Senate Committee on Armed Services projected the overall unit cost of an F-35A to be $112m in today's money.[33] In 2010 Pentagon officials disclosed that the F-35 program has exceeded its original cost estimates by more than 50 percent.[34] An internal Pentagon report critical of the JSF project states that "affordability is no longer embraced as a core pillar".[35]

On 24 March 2010, Gates termed the recent cost overruns and delays as "unacceptable" in a testimony before the U.S. Congress.[35] He characterized previous cost and schedule estimates for the project as "overly rosy". However, Gates insisted the F-35 would become "the backbone of U.S. air combat for the next generation" and informed the Congress that he had expanded the development period by an additional 13 months and budgeted $3 billion more for the testing program while slowing down production.[35]

In August 2010, Lockheed Martin announced delays in resolving a "wing-at-mate overlap" production problem, which would slow initial production.[36]

Design

The F-35 appears to be a smaller, slightly more conventional, single-engine sibling of the sleeker, twin-engine F-22 Raptor, and indeed drew elements from it. The exhaust duct design was inspired by the General Dynamics Model 200 design, which was proposed for a 1972 supersonic VTOL fighter requirement for the Sea Control Ship.[37] For specialized development of the F-35B STOVL variant, Lockheed consulted with the Yakovlev Design Bureau, purchasing design data from their development of the Yakovlev Yak-141 "Freestyle".[38][39] Although several experimental designs have been built and tested since the 1960s including the Navy's unsuccessful Rockwell XFV-12, the F-35B is to be the first operational supersonic STOVL fighter.

The F-35 is designed to be America's "premier surface-to-air missile killer and is uniquely equipped for this mission with cutting edge processing power, synthetic aperture radar integration techniques, and advanced target recognition."[40]

Some improvements over current-generation fighter aircraft are:

- Durable, low-maintenance stealth technology, using structural fiber mat instead of the high-maintenance coatings of legacy stealth platforms;[41]

- Integrated avionics and sensor fusion that combine information from off- and on board sensors to increase the pilot's situational awareness and improve target identification and weapon delivery, and to relay information quickly to other command and control (C2) nodes;

- High speed data networking including IEEE 1394b[42] and Fibre Channel.[43]

- The Autonomic Logistics Global Sustainment (ALGS), Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS) and Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS) help ensure aircraft uptime with minimal maintenance manpower.[44]

- Electrohydrostatic actuators run by a power-by-wire flight-control system.[45]

The majority of the structural composites in the F-35 are made out of bismaleimide (BMI) and composite epoxy material.[46]

Engines

The F-35's main engine is the Pratt & Whitney F135. The General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136 is being developed as an alternate engine.[47] The F135/F136 engines are not designed to supercruise[48] in the F-35. The STOVL versions of both power plants use the Rolls-Royce LiftSystem, patented by Lockheed Martin and built by Rolls-Royce. This system is more like the Russian Yak-141 and German VJ 101D/E[49] than the preceding generation of STOVL designs, such as the Harrier Jump Jet in which all of the lifting air went through the main fan of the Rolls-Royce Pegasus engine.

The Lift System is composed of a lift fan, drive shaft, two roll posts and a "Three Bearing Swivel Module" (3BSM).[50] The 3BSM is a thrust vectoring nozzle which allows the main engine exhaust to be deflected downward at the tail of the aircraft. The lift fan near the front of the aircraft provides a counter-balancing thrust. Somewhat like a vertically mounted turbofan within the forward fuselage, the lift fan is powered by the engine's low-pressure (LP) turbine via a drive shaft and gearbox. Roll control during slow flight is achieved by diverting pressurized air from the LP turbine through wing mounted thrust nozzles called Roll Posts.[51]

The F-35B's lift fan achieves the same 'flow multiplier' effect as the Harrier's huge, but supersonically impractical, main fan. Like lift engines, this added machinery is just dead weight during horizontal flight but provides a net increase in payload capacity during vertical flight. The cool exhaust of the fan also reduces the amount of hot, high-velocity air that is projected downward during vertical take off (which can damage runways and aircraft carrier decks). Though complicated and risky, the lift system has been made to work to the satisfaction of DOD officials.

To date, F136 funding has come at the expense of other parts of the program, reducing the number of aircraft built and increasing their costs.[52] The F136 team has claimed that their engine has a greater temperature margin which may prove critical for VTOL operations in hot, high altitude conditions.[53]

In late 2008 the Air Force revealed that the F-35 would be about twice as loud at takeoff as the F-15 Eagle and up to four times as loud upon landing. As a result, residents near Luke Air Force Base, Arizona and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, possible homes of the jet, have requested that the Air Force conduct environmental impact studies concerning the F-35's noise levels.[54] The city of Valparaiso, Florida, adjacent to Eglin AFB, threatened in February 2009 to sue the Air Force over the impending arrival of the F-35s, but this lawsuit was settled in March 2010.[55][56] Moreover, it was reported in March 2009 that testing by Lockheed Martin and the Royal Australian Air Force revealed that the F-35 was not as loud as first reported, being "only about as noisy as an F-16 fitted with a Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-200 engine" and "quieter than the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor and the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet."[57]

Armament

The F-35 includes a GAU-22/A four-barrel 25mm cannon.[58] The cannon will be mounted internally with 180 rounds in the F-35A and fitted as an external pod with 220 rounds in the F-35B and F-35C.[59][60] The gun pod for the B and C variants will have stealth features. This pod could be used for different equipment in the future, such as EW, reconnaissance equipment, or possibly a rearward facing radar.[61]

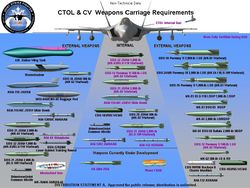

Internally (current planned weapons for integration), up to two air-to-air missiles and two air-to-air or air-to-ground weapons (up to two 2,000 lb bombs in A and C models (BRU-68); two 1,000 lb bombs in the B model (BRU-67)[62]) can be carried in the bomb bays.[63] These could be AIM-120 AMRAAM, AIM-132 ASRAAM, the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) – up to 2,000 lb (910 kg), the Joint Stand off Weapon (JSOW), Small Diameter Bombs (SDB) – a maximum of four in each bay (Three per bay in F-35B[64], or four GBU-53/B in each bay for all F-35 variants.[65]), the Brimstone anti-armor missiles, and Cluster Munitions (WCMD).[63] The MBDA Meteor air-to-air missile is currently being adapted to fit internally in the missile spots and may be integrated into the F-35. The UK had originally planned to put up to four AIM-132 ASRAAM internally but this has been changed to carry 2 internal and 2 external ASRAAMs.[66] It has also been stated by a Lockheed executive that the internal bay will eventually be modified to accept up to 6 AMRAAMs.[67]

At the expense of being more detectable by radar, many more missiles, bombs and fuel tanks can be attached on four wing pylons and two near wingtip positions. The two wingtip locations can only carry AIM-9X Sidewinder. The other pylons can carry the AIM-120 AMRAAM, Storm Shadow, AGM-158 Joint Air to Surface Stand-off Missile (JASSM) cruise missiles, guided bombs, 480-gallon and 600-gallon fuel tanks.[68] An air-to-air load of eight AIM-120s and two AIM-9s is conceivable using internal and external weapons stations, as well as a configuration of six 2,000 lb bombs, two AIM-120s and two AIM-9s.[63][69] With its payload capability, the F-35 can carry more weapons payload than legacy fighters it is to replace as well as the F-22 Raptor.[70] Solid-state lasers were being developed as optional weapons for the F-35 as of 2002.[71][72][73]

Stealth

The F-35 has a low radar cross section primarily due to the materials used in construction, including fibre-mat.[41] The F-35 also has a more stealthy shape than past fighters, including a zigzag-shape weapons bay and landing gear door.

The Teen Series of fighters (F-15, F-16, F/A-18) were notable for always carrying large external fuel tanks, but as a stealth aircraft the F-35 must fly most missions on internal fuel. Unlike the F-16 and F/A-18, the F-35 lacks leading edge extensions (LEX) and instead uses stealth-friendly chines for vortex lift in the same fashion as the SR-71 Blackbird.[61] The small bumps just forward of the engine air intakes form part of the diverterless supersonic inlet (DSI) which is a simpler, lighter and stealthier means to ensure high-quality airflow to the engine over a wide range of conditions.[74]

In spite of being smaller than the F-22, the F-35 has a larger radar cross section. It is said to be roughly equal to a metal golf ball rather than the F-22's metal marble.[75]

Cockpit

The F-35 features a full-panel-width "panoramic cockpit display" (PCD) glass cockpit, with dimensions of 20 by 8 inches (50 by 20 centimeters).[76] A cockpit speech-recognition system (Direct Voice Input) provided by Adacel is planned to improve the pilot's ability to operate the aircraft over the current-generation interface. The F-35 will be the first US operational fixed-wing aircraft to use this system, although similar systems have been used in AV-8B and trialled in previous US jets, particularly the F-16 VISTA.[77] The pilot flies the aircraft by means of a right-hand side stick and left-hand throttle.

A helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) will be fitted to all models of the F-35. A helmet-mounted cueing system is already in service with the F-15s, F-16s and F/A-18s.[78] While some fighters have offered HMDS along with a head up display (HUD), this will be the first time in several decades that a front-line tactical jet fighter has been designed to not carry a HUD.[79]

The Martin-Baker US16E ejection seat is used in all F-35 variants.[80] The US16E seat design balances major performance requirements, including safe-terrain-clearance limits, pilot-load limits, and pilot size. It uses a twin-catapult system that is housed in side rails.[81]

Sensors and avionics

The F-35's sensor and communications suite provides situational awareness, command-and-control and network-centric warfare capability.[82][83] The main sensor on board the F-35 is its AN/APG-81 AESA-radar, designed by Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems.[84] It is augmented by the Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS) mounted under the nose of the aircraft, designed by Lockheed Martin.[85] This gives the same capabilities as the Lockheed Martin Sniper XR without compromising the aircraft's stealth.[86][87]

Six additional passive infrared sensors are distributed over the aircraft as part of Northrop Grumman's AN/AAQ-37 distributed aperture system (DAS),[88] which acts as a missile warning system, reports missile launch locations, detects and tracks approaching aircraft spherically around the F-35, and replaces traditional night vision goggles for night operations and navigation. All DAS functions are performed simultaneously, in every direction, at all times. The F-35's AN/ASQ-239 (Barracuda) Electronic Warfare systems are designed by BAE Systems and include Northrop Grumman components.[89] The communications, navigation and identification (CNI) suite is designed by Northrop Grumman and includes the Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL). The F-35 will be the first jet fighter that has sensor fusion that combines both radio frequency and IR tracking for continuous target detection and identification in all directions which is shared via MADL to other platforms without compromising their low observability.[90]

As a fifth generation fighter, the F-35 is not a federated collection of equipment. All of the sensors feed directly into the main processors to support the entire mission of the aircraft. For example the AN/APG-81 functions not just as a multi-mode radar, but also as part of the aircraft's electronic warfare system.[91]

Unlike older generations of aircraft, such as the F-22, all software for the F-35 is written in C++ for faster code development. The Integrity DO-178B real-time operating system (RTOS) from Green Hills Software runs on COTS Freescale PowerPC processors.[92]

The final Block 3 software for the F-35 is planned to have 8.6 million lines of software code.[93]

The F-35's fifth generation electronic warfare systems are intended to detect hostile aircraft first, which can then be scanned with the electro-optical system and action taken to engage or evade the opponent before the F-35 is detected.[91]

Helmet-Mounted Display System

Rather than maneuvering with thrust vectoring, or canards to line up the target directly ahead of the aircraft, like 4.5 Generation jet fighters, the F-35 does not need to point at the target to hit it. It uses combined radio frequency and infra red (SAIRST) "situational awareness" to continually track all nearby aircraft, the pilot's helmet-mounted display system (HMDS) for displaying and selecting targets, and High Off-Boresight (HOBS) weapons. The helmet system replaces the display suite-mounted head-up display used in previous generation fighters. Because of this, Northrop Grumman claims that "maneuvering is irrelevant".[63][94]

The F-35's systems provide the edge in the "observe, orient, decide, and act" OODA loop; Stealth and advanced sensors aid in observation, automated target tracking helps in orientation, sensor fusion simplifies decision making, and the aircraft's controls allow action against targets without having to look away from them.[95] [N 2]

Concerns over performance

Concerns about the F-35's performance have resulted partially from reports of simulations by RAND Corporation in which numerous Russian Sukhoi fighters defeat a handful of F-35s by denying tanker refueling.[96] As a result of these media reports, then Australian defence minister Joel Fitzgibbon requested a formal briefing from the Australian Department of Defence on the simulation. This briefing stated that the reports of the simulation were inaccurate and that it did not compare the F-35's performance against that of other aircraft.[97]

Maj. Richard Koch, chief of USAF Air Combat Command’s advanced air dominance branch is reported to have said that “I wake up in a cold sweat at the thought of the F-35 going in with only two air-dominance weapons.”[98]

This criticism of the F-35 has been dismissed by the Pentagon and Lockheed Martin as these simulations did not address air-to-air combat.[96][99] RAND has disavowed the critical remarks about the F-35 for the same reason and stated that no analysis was provided at that time regarding the performance of the F-35.[96] The USAF has conducted an analysis of the F-35's air-to-air performance against all 4th generation fighter aircraft currently available, and has found the F-35 to be at least four times more effective. Major General Charles R. Davis, USAF, the F-35 program executive officer, has stated that the "F-35 enjoys a significant Combat Loss Exchange Ratio advantage over the current and future air-to-air threats, to include Sukhois".[99] The Russian, Indian, Chinese, and other air forces operate Sukhoi Su-27/30 fighters.

In a similar RAND Corporation tanker-denial scenario, three regiments of Chinese Sukhoi Su-27s defeated six F-22 Raptors by avoiding the fighters and destroying the refueling tankers.[96]

Andrew Krepinevich has questioned the reliance on a short ranged aircraft like the F-35 to 'manage' China in a future conflict and has called on reducing the F-35 buy in favor of a longer ranged platform like the Next-Generation Bomber, but former United States Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne rejected this plan of action back in 2007.[100][101][102]

Chen Hu, editor-in-chief of World Military Affairs magazine has said that the F-35 is too costly because it attempts to provide the capabilities needed for all three American services in a common airframe.[103] Dutch news program NOVA show interviewed US defense specialist Winslow T. Wheeler and aircraft designer Pierre Sprey who called the F-35 "heavy and sluggish" as well as having a "pitifully small load for all that money", and went on to criticize the value for money of the stealth measures as well as lacking fire safety measures. His final conclusion was that any air force would be better off maintaining its fleets of F-16s and F/A-18s compared to buying into the F-35 program.[104] Like the Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey, the F-35B sends jet thrust directly downwards during vertical takeoffs and landing and the nozzle is being redesigned to spread the output out in an oval rather than a small circle so as to limit damage to asphalt and ship decks.[105]

In the context of selling F-35s to Israel to match the F-15s that will be sold to Saudi Arabia, a senior U.S. defense official was quoted as saying that the F-35 will be "the most stealthy, sophisticated and lethal tactical fighter in the sky," and added "Quite simply, the F-15 will be no match for the F-35."[106]

Manufacturing responsibilities

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics is the prime contractor and performs aircraft final assembly, overall system integration, mission system, and provides forward fuselage, wings and flight controls system. Northrop Grumman provides Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar, Infra red Distributed Aperture System (DAS), Communications, Navigation, Identification (CNI), center fuselage, weapons bay, and arrestor gear. BAE Systems provides aft fuselage and empennages, horizontal and vertical tails, crew life support and escape systems, Electronic warfare systems, fuel system, and Flight Control Software (FCS1). Alenia will perform final assembly for Italy and, according to an Alenia executive, assembly of all European aircraft with the exception of Turkey and the United Kingdom.[107]

As an international program, countries that help build the F-35 will form a competitive marketplace where parts and maintenance contracts are traded.[108] On 24 November 2009, Jon Schreiber said that the United States will not share the software code for the F-35 with its allies.[109]

The F-35 program has seen a great deal of investment in automated production facilities. For example Handling Specialty produced the wing assembly platforms for Lockheed Martin with some of the same technology used in the O (Cirque du Soleil) set.[110]

Next Generation Jammer

The USMC is considering replacing their EA-6B Prowler Electronic Attack aircraft with F-35s that have stealthy jammer pods attached.[111]

On 30 September 2008, the United States Navy outlined the basic requirements of the NGJ and stated that the design must be modular and open.[112] Kent, John R. et al. The Navy has selected four companies to submit designs for the Next Generation Jammer.[113]

The NGJ will also have cyber attack capabilities where the AESA radar is used to insert attack codes into remote systems.[114]

The ITT-Boeing design for the NGJ includes six AESA arrays for all around coverage.[115] The team has been awarded a $42 million contract to develop their design based on ITT's strength with broadband electronically steerable antenna arrays.[116] At the same time contracts were also awarded to Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and BAE Systems.[117]

Operational history

Testing

The first F-35A (designated AA-1) was rolled out in Fort Worth, Texas on 19 February 2006. The aircraft underwent extensive ground testing at Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth in late 2006. In September 2006 the first engine run of the F135 afterburner turbofan in an airframe and tests were completed; the first time that the F-35 was completely functional on its own power systems.[118] On 15 December 2006, the F-35A completed its maiden flight.[13]

A modified Boeing 737-300, the Lockheed CATBird is used as an avionic test bed inside of which are racks holding all of F-35's avionics, as well as a complete F-35 cockpit.

On 31 January 2008 at Fort Worth, Texas, Lt Col James "Flipper" Kromberg of the U.S. Air Force became the first military service pilot to evaluate the F-35, taking the aircraft through a series of maneuvers on its 26th flight.

F-35 AA-1, on its 34th test flight, began aerial refueling testing in March 2008.[119] Another milestone was reached on 13 November 2008, when the AA-1 flew at supersonic speeds for the first time, reaching Mach 1.05 at 30,000 feet (9,144 m) making four transitions through the sound barrier, for a total of eight minutes of supersonic flight.[120]

The first F-35B (designated BF-1) made its maiden flight on 11 June 2008. The flight, which featured a conventional take off, was piloted by BAE Systems' test pilot Graham Tomlinson. The BF-1 is the second of 19 System Development and Demonstration (SDD) F-35s, and the first to use new weight-optimized design features that will apply to all future F-35s.[121] Testing of the STOVL propulsion system in flight began on 7 January 2010. The STOVL system was used for 14 minutes of the 48 minute test flight while the aircraft slowed from 210 knots to 180 knots.[122][123] The F-35B's first hover (full stop in mid-air) happened on 17 March 2010, followed by a STOVL landing,[124] and on 18 March 2010 the first vertical landing was performed.[125] During a test flight on 10 June 2010, the F-35B became the second STOVL aircraft to achieve supersonic speeds,[126] the first being its ancestor, the X-35B, which achieved the same feat on 20 July 2001.[127]

Although many of the initial flight test targets have been accomplished, the F-35 testing program completed "just under 100 sorties and about as many hours in 2.5 years" by June 2009 and was falling significantly behind schedule.[128] A 2008 Pentagon Joint Estimate Team (JET I) estimated that the program was two years behind the latest public schedule, and a 2009 Joint Estimate Team (JET II) revised that estimate to predict a 30-month delay.[129] Due to those delays in the testing program, production numbers will be reduced by 122 aircraft through 2015 in order to provide additional funds for development.[130] Those additional funds will add $2.8 billion to the development funds and internal memos suggest that the official timeline will be extended by 13 months (not the 30 months the JET II team predicted the slip would be).[129] The success of the Joint Estimate Team has led Ashton Carter to call for more such teams for other poorly performing Pentagon projects.[131]

Nearly 30 percent of all the test flights have required more than routine maintenance to get the aircraft flyable again.[132] Currently each F-35 takes a million more work hours than predicted and flight testing is expected to result in further design changes.[133] The United States Navy has projected that lifecycle costs over a fleet life of 65 years for all of the American F-35s will be $442 billion higher than the U.S. Air Force has projected.[134]

The delay in the F-35 program is expected to lead to a shortfall of only around 100 jet fighters in the Navy/Marines team, given careful management, service life extension of the Marines' legacy F/A-18s and more burdens placed on Navy fighters.[2]

The F-35C carrier variant's maiden flight took place on 7 June 2010, also at NAS Fort Worth JRB. The 57 minute flight was executed by Lockheed test pilot Jeff "Slim" Knowles, who was the chief test pilot for the F-117 program.[135]

A total of 11 U.S. Air Force F-35s are to arrive in Fiscal Year 2011.[136]

International participation

While the United States is the primary customer and financial backer, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Canada, Turkey, Australia, Norway and Denmark have agreed to contribute US$4.375 billion toward the development costs of the program.[11] Total development costs are estimated at more than US$40 billion (underwritten largely by the United States), while the purchase of an estimated 2,400 planes is expected to cost an additional US$200 billion.[137] The nine major partner nations plan to acquire over 3,100 F-35s through 2035,[138] making the F-35 one of the most numerous jet fighters.

There are three levels of international participation. The levels generally reflect the financial stake in the program, the amount of technology transfer and subcontracts open for bid by national companies, and the order in which countries can obtain production aircraft. The United Kingdom is the sole "Level 1" partner, contributing US$2.5 billion, which was about 10% of the planned development costs[139] under the 1995 Memorandum of Understanding that brought the UK into the project.[140] Level 2 partners are Italy, which is contributing US$1 billion; and the Netherlands, US$800 million. Level 3 partners are Canada, US$475 million; Turkey, US$195 million; Australia, US$144 million; Norway, US$122 million and Denmark, US$110 million. Israel and Singapore have joined as Security Cooperative Participants (SCP).[141]

Variants

The F-35 is planned to be built in three different versions to suit the needs of its various users.

F-35A

The F-35A is the conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) variant intended for the US Air Force and other air forces. It is the smallest, lightest F-35 version and is the only variant equipped with an internal cannon, the GAU-22/A. This 25 mm cannon is a development of the GAU-12 carried by the USMC's AV-8B Harrier II. It is designed for increased effectiveness compared to the 20 mm M61 Vulcan cannon carried by other USAF fighters.

The F-35A is expected to match the F-16 in maneuverability and instantaneous and sustained high-g performance, and outperform it in stealth, payload, range on internal fuel, avionics, operational effectiveness, supportability, and survivability.[142] It also has an internal laser designator and infrared sensors, equivalent to the Sniper XR pod carried by the F-16, but built in to remain stealthy.

The A variant is primarily intended to replace the USAF's F-16 Fighting Falcon, beginning in 2013, and replace the A-10 Thunderbolt II starting in 2028.[143][144]

F-35B

The F-35B is the short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) variant of the aircraft. Similar in size to the A variant, the B sacrifices some fuel volume to make room for the vertical flight system. Takeoffs and landing with vertical flight systems are by far the riskiest, and in the end, a decisive factor in design. Like the AV-8B Harrier II, the B's guns will be carried in a ventral pod. Whereas F-35A is stressed to 9 g, the F-35B is stressed to 7 g.[145][146] Unlike the other variants, the F-35B has no landing hook; the "STOVL/HOOK" button in the cockpit initiates conversion instead of dropping the hook.[147]

The United Kingdom's Royal Air Force and Royal Navy plan to use this variant to replace their Harrier GR7/GR9s. The United States Marine Corps intends to purchase 340 F-35Bs[148] to replace all current inventories of the F/A-18 Hornet (A, B, C and D-models), and AV-8B Harrier II in the fighter, and attack roles.[149] The USMC is investigating an electronic warfare role for the F-35B to replace the service's EA-6B Prowlers.[150][151]

One of the British requirements was that the F-35B design should have a Ship-borne Rolling and Vertical Landing (SRVL) mode[152] so that wing lift could be added to powered lift to increase the maximum landing weight of carried weapons.[153] This method of landing is slower than wire arrested landing, and could disrupt regular carrier operations. The UK is developing a SRVL (Shipborne Rolling Vertical Landing) method to operate F-35Bs from carriers without disrupting carrier operations landings[154] as the landing method uses the same pattern of approach as wire arrested. With SRVL, the aircraft is able to "bring back" 2 x 1K JDAM, 2 x AIM-120 and reserve fuel.[155]

The F-35B was unveiled at Lockheed Martin's Fort Worth plant on 18 December 2007,[156] and the first test flight was on 11 June 2008.[157] The B variant is expected to be available beginning in 2012.

F-35C

The F-35C carrier variant has a larger, folding wing and larger control surfaces for improved low-speed control, and stronger landing gear and hook for the stresses of carrier landings. The larger wing area allows for decreased landing speed, increased range and payload, with twice the range on internal fuel compared with the F/A-18C Hornet, achieving much the same goal as the heavier F/A-18E/F Super Hornet.

The United States Navy will be the sole user for the carrier variant. It intends to buy 480 F-35Cs to replace the F/A-18A, B, C, and D Hornets. The F-35C will also serve as a stealthier complement to the Super Hornet.[158] On 27 June 2007, the carrier variant completed its Air System Critical Design Review (CDR). This allows the first two functional prototype F-35C units to be produced.[159] The C variant is expected to be available beginning in 2014.[160] The first production F-35C was rolled out on 29 July 2009.[161]

F-35I

F-35A with Israeli modifications as above.

Specifications (F-35A)

| F-35B Lightning II cutaway illustration | |

|---|---|

| Hi-res cutaway of F-35B Lightning II STOVL by Flight Global, 2006. | |

Data from Lockheed Martin specifications,[162][163][164] F-35 Program brief,[63] F-35 JSF Statistics[59]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 51.4 ft (15.67 m)

- Wingspan: 35 ft (10.7 m)

- Height: 14.2 ft[nb 1] (4.33 m)

- Wing area: 460 ft²[63] (42.7 m²)

- Empty weight: 29,300 lb (13,300 kg)

- Loaded weight: 49,540 lb[165][nb 2][166] (22,470 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 70,000 lb[nb 3] (31,800 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Pratt & Whitney F135 afterburning turbofan

- Dry thrust: 28,000 lbf[167][nb 4] (125 kN)

- Thrust with afterburner: 43,000 lbf[167][168] (191 kN)

- Internal fuel: 18,480 lb (8,382 kg)[nb 5]

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.67[169] (1,283 mph, 2,065 km/h)

- Range: 1,200 nmi (2,220 km) on internal fuel

- Combat radius: 590 nmi (1,090 km) on internal fuel[170]

- Service ceiling: 60,000 ft[171] (18,288 m)

- Rate of climb: classified (not publicly available)

- Wing loading: 91.4 lb/ft² (446 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight:

- With full fuel: 0.87

- With 50% fuel: 1.07

- g-Limits: 9 g[nb 6]

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 25 mm (0.984 in) GAU-22/A cannon, internally mounted with 180 rounds[nb 7][59]

- Hardpoints: 6 × external pylons on wings with a capacity of 15,000 lb (6,800 kg)[59][63] and 2 × internal bays with 2 pylons each[63] for a total weapons payload of 18,000 lb (8,100 kg)[162] and provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles:

- Air-to-air: AIM-120 AMRAAM, AIM-132 ASRAAM, AIM-9X Sidewinder, IRIS-T, Joint Dual Role Air Dominance Missile (JDRADM) (after 2020)[172]

- Air-to-ground: AGM-154 JSOW, AGM-158 JASSM[69]

- Bombs:

- Missiles:

Avionics

- Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems AN/APG-81 AESA radar

Differences across variants

- ↑ B is the same, C: 14.9 ft (4.54 m)

- ↑ F-35B: 47,996 lb (21,771 kg); F-35C: 57,094 lb (25,896 kg)

- ↑ C is same, B: 60,000 lb (27,000 kg)

- ↑ F-35B: vertical thrust 39,700 lbf (176 kN)

- ↑ F-35B: 14,003 lb (6,352 kg); F-35C: 20,085 lb (9,110 kg)

- ↑ F-35B: 7.5 g, F-35C: 7.5 g

- ↑ F-35B and F-35C have cannon in an external pod with 220 rounds

| F-35A CTOL |

F-35B STOVL |

F-35C Carrier version |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 51.4 ft (15.7 m) | 51.3 ft (15.6 m) | 51.5 ft (15.7 m) |

| Wingspan | 35 ft (10.7 m) | 35 ft (10.7 m) | 43 ft (13.1 m) |

| Wing Area | 460 ft² (42.7 m²) | 460 ft² (42.7 m²) | 668 ft² (62.1 m²) |

| Empty weight | 29,300 lb (13,300 kg) | 32,000 lb (14,500 kg) | 34,800 lb (15,800 kg) |

| Internal fuel | 18,500 lb (8,390 kg) | 13,300 lb (6,030 kg) | 19,600 lb (8,890 kg) |

| Max takeoff weight | 70,000 lb (31,800 kg) | 60,000 lb (27,000 kg) | 70,000 lb (31,800 kg) |

| Range | 1,200 nmi (2,220 km) | 900 nmi (1,670 km) | 1,400 nmi (2,520 km) |

| Combat radius | 590 nmi (1,090 km) | 450 nmi (833 km) | 640 nmi (1,110 km) |

| Thrust/weight full fuel 50% fuel |

0.87 1.07 |

0.90 1.04 |

0.75 0.91 |

Media

| Official JSF program videos |

See also

- Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II procurement

Related development

- Lockheed Martin X-35

- F-22 Raptor

Comparable aircraft

- Sukhoi PAK FA

- Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft

Related lists

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of megaprojects, Aerospace

References

- Notes

- ↑ Quote: "The F-35 Lightning II will carry on the legacy of two of the greatest and most capable fighter aircraft of all time," said Ralph D. Heath, president of Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co. "Just as the P-38 and the British Lightning were at the top of their class during their day, the F-35 will redefine multi-role fighter capability in the 21st century."

- ↑ Quote: "Brigadier Davis was more forthright in his comments to media in Canberra, saying the ‘Raptor’ lacks some of the key sensors and the enhanced man-machine interface of the F-35."

- Citations

- ↑ "F-35 First Flight." TeamJSF.com. Retrieved: 10 October 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Grant, Greg "JSF Production “Turned The Corner." dodbuzz.com. Retrieved: 15 April 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Lightning II Program Update & Fast Facts." lockheedmartin.com. Retrieved: 26 August 2010.

- ↑ Rogin, Josh. "Report: F-35 Work Falls Behind Two More Years." CQ Politics, 23 July 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "US announces two-year delay in F-35 fighter program." AFP, 2010. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Scully, Megan. "Navy acknowledges schedule for F-35 fighter is slipping." govexec.com, 12 March 2010. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II". Jane's All the World's Aircraft. (online version, 21 January 2008).

- ↑ McKinney, Brooks. "Northrop Grumman Begins Assembling First F-35 Production Jet." Northrop Grumman, 1 April 2008. Retrieved: 19 April 2008. (Less than eight were completed prior to 1 April 2008.)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "FY 2011 Budget Estimates", p. 1–1/47. United States Air Force, February 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "F-35 Capabilities." Lockheed Martin, 2009. Retrieved: 9 February 2009.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Lightning II – International Partners." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 7 April 2010.

- ↑ "JSF program history." JSF.mil.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Warwick, Graham. "F-35 Lighting II Joint Strike Fighter first flight – short but sweet." Flight International, 15 December 2006.

- ↑ "Pentagon's F-35 Fighter Under Fire in Congress." pbs.org. Retrieved: 22 Augusut 2010.

- ↑ "Lockheed F-35 to beat Pentagon estimate by 20 pct." Reuters. Retrieved: 22 August 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Lightning II." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "Lockheed Martin sees F-35A replacing USAF air superiority F-15C/Ds." flightglobal.com, 4 February 2010. Retrieved: 2 March 2010.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Keijsper 2007, p. 119.

- ↑ "Designation Systems." Designation Systems. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. and Robert Wall. "USAF Plans for Fighters Change." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 19 September 2004. Retrieved: 8 February 2006.

- ↑ Keijsper 2007, p. 124.

- ↑ "'Lightning II' moniker given to Joint Strike Fighter." Air Force Link, United States Air Force, 7 June 2006. Retrieved: 1 December 2008.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin Joint Strike Fighter Officially Named 'Lightning II.'" Lockheed Martin press release, 7 July 2006 Retrieved: 28 May 2009.

- ↑ Kent, John R. and Joseph W. Stout. "Weight-Optimized F-35 Test Fleet Adds Conventional Take off And Landing Variant." Lockheed Martin, 23 December 2008. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Moore, Mona. "F-35 production on target." Northwest Florida Daily News, 5 January 2009, Volume 62, Number 341, p. A1.

- ↑ Gearan, Anne. "Defense Secretary Gates proposes weapons cuts." Seattle Times, 7 April 2009.

- ↑ Fishel, Justin and the Associated Press. "Gates Calls for Cuts to High-Tech Weapons Programs." Fox News, 6 April 2009. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Gorman, Siobhan. "Computer Spies Breach Fighter-Jet Project." The Wall Street Journal, 21 April 2009. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Cullen, Simon. "Jet maker denies F-35 security breach." Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 22 April 2009. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Bennett, John T. "Plan Afoot to Halt F-35 Cost Hikes, Delays." defensenews.com, 9 November 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Clark, Colin. "Gates Fires JSF Program Manager." dodbuzz.com, 1 February 2010. Retrieved: 21 March 2010.

- ↑ Cox, Bob. "Gates criticizes F-35 progress, fires top officer." star-telegram.com. Retrieved: 21 March 2010.

- ↑ "JSF faces US Senate grilling." australianaviation.com.au, 12 March 2010.

- ↑ Shalal-Esa, Andrea and Tim Dobbyn, ed. "Price of F35 fighter soars." reuters.com. Retrieved: 21 March 2010.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Thompson, Mark. "The Costly F-35: The Saga of America's Next Fighter Jet." Time, 25 March 2010. Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "Fix for F-35 final assembly problem pushed back." flightglobal.com, 16 August 2010. Retrieved: 24 August 2010.

- ↑ "Vertiflight". Journal of the American Helicopter Society. January 2004.

- ↑ Hayles, John. "Yakovlev Yak-41 'Freestyle'". Aeroflight, 28 March 2005. Retrieved: 3 July 2008.

- ↑ "Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)." Jane's. Retrieved: 3 July 2008.

- ↑ "Air Force presentation to House Subcommittee on Air and Land Forces." armedservices.house.gov, 20 May 2009, page 10. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Butler, Amy. "New Stealth Concept Could Affect JSF Cost." aviationweek.com, 17 May 2010. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ Philips, E. H. "The Electric Jet." Aviation Week & Space Technology, 5 February 2007.

- ↑ Parker, Ian. "Reducing Risk on the Joint Strike Fighter." Avionics Magazine, Access Intelligence, LLC, 1 June 2007. Retrieved: 8 June 2007.

- ↑ Giese, Jack. "F-35 Brings Unique 5th Generation Capabilities." lockheedmartin.com, 23 October 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "Farnborough: Lockheed encouraged by pace of F-35 testing." flightglobal.com, 12 June 2010. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Contract Awarded To Validate Process For JSF." onlineamd.com, 17 May 2010. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "Rolls-Royce: F136 survival is key for major F-35 engine upgrade." Flight International, 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about JSF." JSF.mil. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Swivel nozzle VJ101D and VJ101E." Vstol.org, 20 June 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "LiftSystem." Rolls-Royce. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Hutchinson, John. "Going Vertical: Developing a STOVL system." ingenia.org.uk. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Warwick, Graham. "Second Engine Could Cut F-35 Production." aviationweek.com. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "GE Rolls-Royce Fighter Engine Team completes study for Netherlands." rolls-royce.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Alaimo, Carol Ann. "Noisy F-35 Still Without A Home." Arizona Daily Star, 30 November 2008. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Moore, Mona. "Val-P to sue the Air Force." Northwest Florida Daily News, Thursday, 19 February 2009, Volume 63, Number 20, page A1.

- ↑ Barlow, Kari C. "Val-p wants Okaloosa to reimburse F-35 legal fees." thedestinlog.com, 16 April 2010.

- ↑ Perrett, Bradley. "F-35 May Need Thermal Management Changes." Aviationweek.com, 12 March 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "F-35 gun system." General Dynamics Armament and Technical Products.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Media Kit Statistics(ZIP, 98.2 KB)." JSF.mil, August 2004.

- ↑ "F-35 specifications." GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bolsøy, Bjørnar. "F-35 Lightning II status and future prospects." f-16.net, 17 September 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Suite.htm JSF Suite: BRU-67, BRU-68 Bomb Rack Units and LAU-147 Launcher

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 63.5 63.6 63.7 Davis, Brigadier General Charles R. "F-35 Program Brief." USAF, 26 September 2006. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ F-35B STOVL Variant

- ↑ "Small Diameter Bomb II - GBU-53/B." defense-update.com. Retrieved: 28 August 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Lightning II News: ASRAAM Config Change For F-35." f-16.net, 4 March 2008.

- ↑ "Amraams." Aviationweek.com, 8 November 2007. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Keijsper 2007, p. 239.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Digger, Davis. "JSF Range & Airspace Requirements." Headquarters Air Combat Command, Defense Technical Information Center, 30 October 2007. Retrieved: 3 December 2008.

- ↑ Smith, W. Thomas Jr. "More Fighter than Pilot: Meet the new F-35 Lightning II." National Review, 15 January 2007. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. "Lasers being developed for F-35 and AC-130." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 8 July 2002. Retrieved: 8 February 2006.

- ↑ Morris, Jefferson. "Keeping cool a big challenge for JSF laser, Lockheed Martin says." Aerospace Daily, 26 September 2002. Retrieved: 3 June 2007.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. "Lasers, HPM weapons near operational status." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 22 July 2002. Retrieved: 8 February 2006.

- ↑ Hehs, Eric. "JSF Diverterless Supersonic Inlet." codeonemagazine.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Lightning II." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg. "The Lockheed Martin F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)." vectorsite.net. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Schutte, John. "Researchers fine-tune F-35 pilot-aircraft speech system." US Air Force, 10 October 2007.

- ↑ "Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System." Boeing.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "VSI's Helmet Mounted Display System flies on Joint Strike Fighter." Rockwell Collins, 2007. Retrieved: 8 June 2008.

- ↑ "Martin-Baker." Jsf.org.uk. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Martin-Baker, UK." Martin-baker.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ McHale, John. "F-35 avionics: an interview with the Joint Strike Fighter's director of mission systems and software." militaryaerospace.com. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Capabilities." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "APG-81 (F-35 Lightning II)." Northrop Grumman Electronic Systems. Retrieved: 4 August 2007.

- ↑ Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control: Joint Strike Fighter Electro-Optical Targeting System. Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 11 April 2008.

- ↑ Scott, William B. "Sniper Targeting Pod Attacks From Long Standoff Ranges." Aviationweek.com, 3 October 2004. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Pappalardo, Joe. "How an F-35 Targets, Aims and Fires Without Being Seen." popularmechanics.com, December 2009. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Distributed Aperture System (EO DAS)." Northrop Grumman . Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "JSF EW Suite." istockanalyst.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Nativi, Andy. "F-35 Air Combat Skills Analyzed." Military.com, 6 March 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Sherman, Ron. "F-35 Electronic Warfare Suite: More Than Self-Protection." aviationtoday.com, 1 July 2006. Retrieved: 22 August 2010.

- ↑ McHale, John. "F-35 Joint Strike Fighter leverages COTS for avionics systems." mae.pennnet.com. Retrieved: 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Warwick, Graham. "Flight Tests Of Next F-35 Block Underway." aviationweek.com, 12 June 2010. Retrieved: 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Distributed Aperture System EO DAS." Youtube.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "JSF: the first complete ‘OODA Loop’ aircraft." Australian Defence Business Review, December 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 Trimble, Stephen. "US defence policy - and F-35 - under attack." Flight International, Reed Business Information, 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "Fighter criticism 'unfair' and 'misrepresented'." ABC News, 25 September 2008. Retrieved: 30 October 2008.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill. "JSF Leaders Back In The Fight." aviationweek.com, 22 September 2008. Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Kent, John R. "Setting the Record Straight On F-35". Lockheed Martin, 19 September 2008.

- ↑ Clark, Colin. "Strategy, What Strategy?" dodbuzz.com, 29 June 2010. Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ Kosiak, Steve and Barry Watts. "US Fighter Modernization Plans: Near-term Choices." Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ Wolf, Jim. "Air Force chief links F-35 fighter jet to China." reuters.com, 19 September 2007. Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 fighter has become a clumsy white elephant." globaltimes.cn, 24 March 2010. Retrieved: 3 August 2010.

- ↑ "Airforces better off to keep older planes." Nova, 12 July 2010. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Clark, Colin. "JSF Heat Woes Being Fixed: Trautman." dodbuzz.com, 19 July 2010. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Entous, Adam. "U.S.-Saudi Arms Plan Grows to Record Size: Addition of Apaches, Black Hawks Swells Deal to $60 Billion." online.wsj.com, 14 August 2010. Retrieved: 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Italy Wins JSF Final Assembly: U.K. Presses Maintenance, Support." Aviationnow.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ McDowell, Adam. "Canada needs to update its aging fleet of CF-18s, but when will Ottawa get around to it?" nationalpost.com, 11 March 2010. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Wolf, Jim. "Exclusive: US to withhold F-35 fighter software codes." reuters.com, 24 November 2009. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Handling Specialty Turn Key Capabilities

- ↑ Butler, Amy and Douglas Barrie. "Stealthy Jammer Considered for F-35." Aviationweek.com, 15 June 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Next Generation Jammer Technology Maturation Studies Broad Agency Announcement." navair.navy.mil, 30 September 2008. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "US Navy starts next-generation jammer bidding war." Flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. "U.S. Navy Wants To Field Cyber-Attack System." aviationweek.com, 31 March 2010. Retrieved: 1 April 2010.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. and Bill Sweetman."Jammer Competition Spurs New Technology." aviationweek.com, 28 May 2010. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ Dench, John. ITT/ "Boeing Next Generation Jammer Team Wins $42 Million Navy Award to Mature Technology."marketwatch.com, 16 July 2010. Retrieved: 18 July 2010.

- ↑ "Navy awards jammer contracts."spacewar.com, 15 July 2010. Retrieved: 18 July 2010.

- ↑ "Mighty F-35 Lightning II Engine Roars to Life." Lockheed Martin, 20 September 2006. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin F-35 Succeeds in First Aerial Refueling Test." Lockheed Martin, 13 March 2008.

- ↑ ""Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II Flies Supersonic." Lockheed Martin, 14 November 2008. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "F-35B Stovl Stealth Fighter Achieves Successful First Flight". Lockheed Martin, 11 June 2008. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin F-35B Begins In-Flight STOVL Operations." Lockheed Martin, 7 January 2010. Retrieved: 13 January 2010

- ↑ "News Breaks: F-35B Engages Stovl Mode." Aviation Week, 11 January 2010, p. 15.

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin F-35B STOVL Jet Demonstrates Hover and Short Takeoff Capability." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 18 March 2010.

- ↑ Wolf, Jim (2010). F-35 fighter makes first vertical landing. Reuters. 18 March 2010. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.

- ↑ Cavas, Christopher P. "F-35B STOVL fighter goes supersonic." Marine Corps Times, 15 June 2010. Retrieved: 15 June 2010.

- ↑ "X-planes". PBS: Nova transcript. Retrieved: 9 January 2010.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill. "Get out and fly." Defense Technology International, June 2009, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Cox, Bob. "Internal Pentagon memo predicts that F-35 testing won't be complete until 2016." Fort Worth Star Telegram. 1 March 2010. Retrieved: 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Capaccio, Tony. "Lockheed F-35 Purchases Delayed in Pentagon’s Fiscal 2011 Plan." businessweek.com, 6 January 2010. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Bennett, John T. "Carter: More U.S. Programs To Get JET Treatment." defensenews.com, 29 March 2010. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Thompson, Loren B. "F-35 Cost Rise Is Speculative, But Progress Is Real." lexingtoninstitute.org, 12 March 2010. Retrieved: 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "Senate Armed Services Committee Holds Hearing on President Obama's Fiscal 2011 Budget Request for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program." Congressional Record via startelegram.typepad.com, 11 March 2010. Retrieved: 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "USAF Disputes Navy F-35 Cost Projections." aviationweek.com. Retrieved: 3 July 2010.

- ↑ "Update: U.S. Navy Version of Lockheed Martin F-35 Makes First Flight." Lockheed Martin, 7 June 2010. Retrieved: 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Rolfsen, Bruce. "Jobs to change with focus on irregular warfare." Army Times Publishing Company, 16 May 2010. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ Merle, Renae. "GAO Questions Cost Of Joint Strike Fighter." Washington Post, 15 March 2005. Retrieved: 15 July 2007.

- ↑ "Estimated JSF Air Vehicle Procurement Quantities." JSF.mil, April 2007. Retrieved: 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "JSF Global Partners." teamjsf.com. Retrieved: 30 March 2007.

- ↑ "US, UK sign JAST agreement." Aerospace Daily New York: McGraw-Hill, 25 November 1995, p. 451.

- ↑ Schnasi, Katherine V. "Joint Strike Fighter Acquisition: Observations on the Supplier Base." US Accounts Office. Retrieved: 8 February 2006.

- ↑ Pike, John. "F-35A Joint Strike Fighter." Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Hebert, Adam J. "Lightning II: So Far, So Good." airforce-magazine.com, Air Force Association, Volume 90, Issue 7, July 2007. Retrieved: 3 December 2008.

- ↑ Laurenzo, Ron. "Air Force: No Plan To Retire A-10." GlobalSecurity.org, Defense Weekly, 9 June 2003. Retrieved: 3 December 2008.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill. "Numbers Crunch: True cost of JSF program remains to be seen." Defense Technology International, February 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ "F-35 HMDS Pulls the Gs". Defense Industry Daily, 25 October 2007.

- ↑ Majumdar, Dave. "Ride the Lightning: Testing the Marine Corps' latest fighter." examiner.com, 27 March 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Fourth F-35 Lightning II Rolls Out as Production Line Fills Up at Lockheed Martin." FOXBusiness.com, Comtex, FOX News Network, LLC, 18 August 2008. Retrieved: 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "US Marine Corps aviation branch plans to invest in fighter jets, helicopters, transports and UAVs." Flight International, Reed Business Information, 21 July 2008. Retrieved: 21 July 2008.

- ↑ Fulghum, David A. "Electronic Attack Plan Nears Approval." Aviation Week, Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, 4 June 2008. Retrieved: 8 August 2008.

- ↑ "Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Transition Plan." usmc.mil. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Major Projects Report 2008." Ministry of Defence. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Millard, Douglas. "QinetiQ proves its innovative Bedford Array visual landing aid on HMS Illustrious." Qinetiq.com. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "US Marines eye UK JSF shipborne technique." Flightglobal.com, 15 June 2007. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "CRS RL30563, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, , p. 106." opencrs.com, 16 September 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "First Short Takeoff/Vertical Landing Stealth Fighter Unveiled at Lockheed Martin." Marine Corps News, 18 December 2007. Retrieved: 18 December 2007.

- ↑ Norris, Guy and Graham Warwick. "F-35B First Flight Boosts JSF as F-22 Loses Supporters." Aviation Week, 15 June 2008.

- ↑ "F-35C Carrier Variant Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 16 June 2010.

- ↑ "F-35 Navy Version Undergoes Successful Design Review, Readies for Production." Lockheed Martin, 7 June 2007. Retrieved: 16 June 2010.

- ↑ Grant, Rebecca L., Ph.D. "Navy Speeds Up F-35." Lexington Institute, 14 September 2009. Retrieved: 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "F-35C Lightning II rolled out." FrontierIndia.net, 29 July 2009.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 "F-35A - CTOL." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "F-35B STOVL." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "F-35C - CV." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 28 July 2010.

- ↑ Nativi, Andy. "F-35 Air Combat Skills Analyzed". Aviation Week, 5 March 2009. Quote: "The F-35A, with an air-to-air mission takeoff weight of 49,540 lb"

- ↑ "F-35 variants." jsf.mil. Retrieved: 22 August 2010.

- ↑ 167.0 167.1 "The Pratt & Whitney F135". Jane's Aero Engines. Jane's Information Group, 2009. (subscription version, dated 10 July 2009).

- ↑ "Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II". Jane's All the World's Aircraft. Jane's Information Group, 2010. (subscription article, dated 1 February 2010).

- ↑ Nativi, Andy. "F-35 Air Combat Skills Analyzed." Aviation Week , 5 March 2009. Retrieved: 15 August 2009.

- ↑ "F-35 brochure, p. 6." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 1 April 2009.

- ↑ "LockheedMartin F-35B JSF." Airtoaircombat.com. Retrieved: 15 August 2009.

- ↑ 2010 Precision Strike Winter Roundtable

- ↑ "NNSA Seeks $40M for Nuke Refurbishment Study." globalsecuritynewswire.org. Retrieved: 5 June 2010.

- ↑ "Managing the U.S. Nuclear Deterrent, Strat Com, p. 10." fas.org. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Tirpak, John A. "The Nuclear F-35." airforce-magazine.com, 12 May 2009. Retrieved: 23 November 2009.

- ↑ "Nuclear Posture Review Report." defense.gov, April 2010. Retrieved: 7 April 2010.

- Bibliography

- Borgu, Aldo. A Big Deal: Australia's Future Air Combat Capability. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2004. ISBN 1-92072-225-4.

- Gunston, Bill. Yakovlev Aircraft since 1924. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1997. ISBN 1-55750-978-6.

- Keijsper, Gerald. Lockheed F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. London: Pen & Sword Aviation, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84415-631-3.

- Kopp, Carlo and Peter Goon. "Joint Strike Fighter." Air Power Australia. Retrieved: 15 July 2007.

- Spick, Mike. The Illustrated Directory of Fighters. London: Salamander, 2002. ISBN 1-84065-384-1.

- Winchester, Jim. "Lockheed Martin X-35/F-35 JSF." Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft. Kent, UK: Grange Books plc., 2005. ISBN 1-59223-480-1.

External links

- Official JSF web site

- Official Team JSF industry web site

- JSF UK Team

- F-35 - Royal Air Force

- US Navy Research, Development & Acquisition, F-35 page

- F-35 - Global Security

- F-35 profile and F-35 weapons carriage on Aerospaceweb.org

- F-35 Lightning II News on f-35jsf.net

- F-35B Roll out pictures

- F-35 Article - Armed Forces

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||